category: full-length play

genre: epic

running time: two hours

setting: various locations in modern America and ancient Babylon

period: contemporary/mythical times

characters:

Vincent, an artist, late twenties, homosexual

Celeste, his twin sister

Jack, an amiable straight man in his mid-twenties

Gilgamesh, the quasi-divine king of Uruk

Rimat-Ninsun, his mother, a prophetess

Enkidu, his companion

Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love

Shamash, the Babylonian god of the sun

Ereshkigal, the Babylonian goddess of death

Shamhat, a priestess of Ishtar

Ziusudra, the survivor of the great flood

Ziusudra’s Wife, a minor goddess

Siduri, an innkeeper

Humbaba, a three-headed monster

The Trapper, a game hunter

The Scorpion Man and His Mate

story:

Vincent is a modern day man, a successful artist living off illustrating science books, haunted by the memory of his deceased father and afraid to connect with other men, despite his attraction to the amiable but unavailable Jack. Gilgamesh is the king of ancient Babylon, half-human and half-god, imperiously powerful but living a life devoid of any meaning. One day a mysterious, half-wolf creature enters his realm and is trapped by the priestess Shamhat, who transforms him into a full human being: the hero Enkidu. Immediately attracted to one another, Enkidu helps Gilgamesh slay the three-headed monster, Humbaba. Sadly, the companions anger the goddess Ishtar and Enkidu is struck down, his death breaking Gilgamesh’s heart and reducing him to human status. Meanwhile, Vincent has been growing closer to Jack but is terrified of opening up to him when he knows they can never be lovers, and despite support from his sister Celeste he begins to think he might be going crazy from isolation and fears of intimacy. Confused and lonely in their own worlds, the two men stumble into a juxtaposition and meet. Moved by Gilgamesh’s love for Enkidu, Vincent assumes a role as his guide on the journey to retrieve his immortality from Ziusudra, the oldest man in the world. Together they travel through the wastelands and the lands of the Scorpion People until they come to the Sacred Garden of Ziusudra, who advises Gilgamesh to turn the loss of Enkidu into a story which will outlast all of their lifetimes. In the modern world, Vincent and Jack sit down and have coffee together, and slowly begin a friendship that Shamhat predicts will change their lives.

author’s comments:

Of everything I have ever written, this still teaches me stuff every time I look back at it- about writing and life. There are moments in our lives when we touch something bigger and better than us and this was the result of one of those times. It probably helps that I believed I was more or less dying- no doubt because I was getting closer to finishing college, which is almost the same thing when you’re a twenty-something in America with a degree in English and no job prospects. In reality, my father was dying and my ex-lover who I had been very close to had decided to stop speaking to me, and those elements also figure heavily in the work. The first act, in particular, is dark, even for me, and the scene in which Enkidu dies is filled with more bile and despair than any other sequence in my current canon. By the weird logic of the art universe, the play also transcends to greater depths of beauty than I’d ever previously achieved, and the blending of the modern and ancient worlds somehow freed up both my imagination and my linguistic sensibility to boldly go where I had never really gone before. Unlike Endymion, which is really the precursor to this show, I didn’t write Vincent with an audience sensibility; the play is very funny in places but there is no pandering, and in the bad places the eye doesn’t turn away or attempt to make more dignified the tragedies of loss and rejection, of souls shutting down and petty fears; conversely the sexual element which runs heavy in both plays is much more under the surface of Vincent, and in my opinion the more subtle eroticism of the text makes for a better, more complicated story, the essence of which is a romantic friendship devoid of sex while also being a testimony to the power of sex and love as a transformative act- Shamhat, after all, being the most powerful figure in the play. The child-parent relationships in this play are also far more developed than they had been in anything I’d written before, and what I love about this show is that it’s sort of unique in the sea of plays out there about why mommy and daddy are responsible for how messed up we all are. In Vincent the parents are all really good people and really love their children, and the familial problems don’t come from within the families themselves, but the individuals in question who can’t relate to anyone, let alone the people who created them. There is a constant back and forth regarding the nature of our origins versus the people we think we are and want to be, versus the great equalizers of death and love that cut through all that self-construction and reduce us (or elevate us, depending on your perspective) to the truth and what really matters: this time we have on earth, and how we retain the ability, in spite of everything, to continue to engage with it, since engaging is the only way we can hope to make this meaningless existence meaningful. In the end, though, it is simply a testimony to the mythical act of living, and when all the wonder is said and done the final scene in the coffee shop between Jack and Vincent remains the most affecting for me, whether the play is done with a bare stage and minimal costumes, or bright lights and magnificent splendor. The critic for the Arizona Daily Star, Kathy Allen, heavily championed the Horror Unspeakable production of Vincent, calling the play brave, filled with ideas, and claiming it “borders on the poetic.” She even nominated it for “Drama of the Year” in 2001, giving us the distinction of being the only non-professional, non-Equity company to receive a nomination in that category. Pragmatic gratitude for her support aside, I was mostly blown away that someone else could care about this play as much as I do, because I’ve always thought it so personal, perhaps even cryptically so in places, and when a few years later Anne Heintz took the show to Australia, where it was very well-received, I was again a touch shocked to find out that people not only get it, but love it. But whether that’s a testimony to me, or the universal power of mythology, remains to be seen since the show still hasn’t received a major production with an extensive run. Of everything I have written, it’s the one I’d most like to see crack that last, impossible border between reality and dream.

Productions:

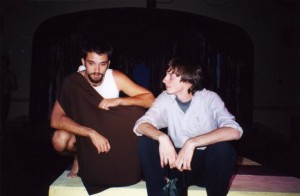

Reed College, March 30 & 31, April 1, 2000, in Winch-Capehart at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Directed by Stuart Bousel; Costumes by Sarah Champ; Masks by Lindsey Cook & Sarah Elizabeth Wilson; Stage Managed by Elizabeth Samuels. Cast: William Cremer (Vincent), Nicholas Nelson (Gilgamesh), Anne Michelson (Celeste/Shamhat), Patrick Stockstill (Jack/Enkidu/Ziusudra), Deborah Strickland (Rimat-Ninsun/Siduri/Humbaba), Tracy Pickels (Ishtar/Humbaba/Ziusudra’s Wife), Francis “Butch” Malec (Shamash/The Trapper/Scorpion Man), Valerie Beck (Ereshkigal/Humbaba/Scorpion Woman)

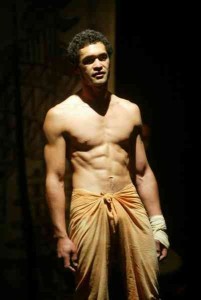

Horror Unspeakable Productions, June 14, 15, 16, 21, 22 & 23, 2001, Cabaret Theater at The Temple of Music and Art, in Tucson, Arizona. Directed by Stuart Bousel; Assistant Directed by April de Luna; Costumes by Stuart Bousel; Lighting by Tonja Goetz; Sound by Lisa Fowle; Scenery by Joshua Galyen & Stuart Bousel; Stage Managed by Joshua Galeyn. Cast: Nat Cassidy (Vincent), Jim Driscoll-MacEachron (Gilgamesh), July Smith (Celeste/Shamhat), Brian McGrath (Jack/Enkidu/Ziusudra), Anne Heintz (Rimat Ninsun/Humbaba/Siduri/Ziusudra’s Wife), Gabrielle Bruwer (Ishtar-Ereshkigal/Humbaba/Scorpion Woman), Joshua Hanna (Shamash/The Trapper/Humbaba/Scorpion Man)

Melbourne Fringe Festival, October 17, 18 & 19, 2003, Loft 6 part of the Melbourne Fringe Festival, Chapel off Chapel- The Loft in Melbourne, Australia. Directed by Anne Heintz; Costumes by Rebecca Etchell; Lighting by Benjamin Watts; Scenery by Rebecca Etchell; Sound by Robert Harewood; Music/Djembe by Naomi Henderson. Cast: Daniel Fletcher (Vincent), Phillip Haby (Gilgamesh), Anne Heintz, (Celeste/Shamhat), Che Timmins (Jack/Enkidu), Sadie Wells (Rimat-Ninsun/Humbaba), Leni Upson (Ishtar-Ereshkigal/Humbaba), William Tait (Shamash/Trapper/Humbaba)